Review: Alexei Ratmansky Unleashes the Pain of War at City Ballet

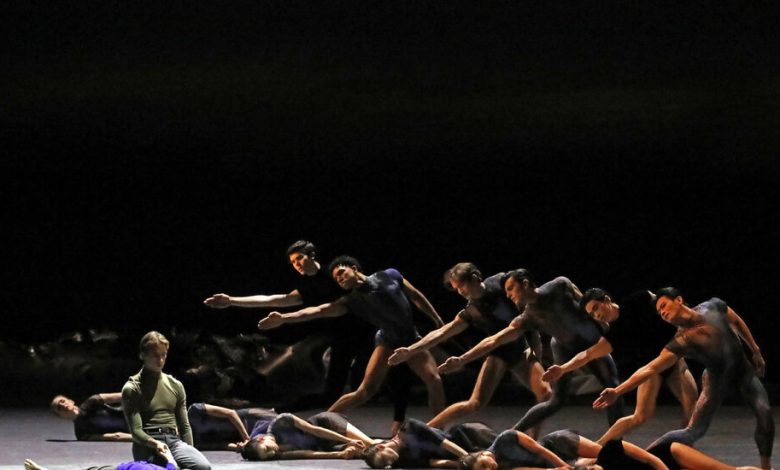

How does a body stand upright when the world is spinning around it? Or, worse, when that world is breaking down with such vehemence that the air seems to grow more toxic by the minute? In Alexei Ratmansky’s new ballet “Solitude,” dancers waver and buckle as inner and outer forces wreak havoc on their bodies. Within this stark, dark universe, set to music by Gustav Mahler, bodies live on the edge, leaning and bending precariously as they fight for equilibrium. They are disjointed, their body parts at odds with one another. Spines twist deeply, as if wringing out the torso could also unleash the rawest pain.

Ratmansky’s latest ballet, his first as artist in residence at New York City Ballet, is about war — the devastating war in Ukraine, the country where Ratmansky grew up and where his parents still live. This month marks two years since the Russian invasion, and there seems to be no end in sight.

Dedicated to “the children of Ukraine, victims of the war,” the ballet, which had its premiere on Thursday at the David H. Koch Theater, was inspired by a photograph of a father kneeling next to the body of his 13-year-old son after he was killed by a Russian airstrike at a bus stop in Kharkiv. The father held the boy’s hand for hours.

That grief — the solitude of “Solitude” — is apparent from the start. The principal dancer Joseph Gordon kneels before the limp body of Theo Rochios, a young student of the company-affiliated School of American Ballet. Rochios, in a bright blue shirt — it lets him nearly glow in the darkness — lies flat on his back while Gordon holds his hand.

The motionless form of Gordon, wearing pants and a tight army-green turtleneck that calls to mind Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, is searing. Couples spring onto the stage from the opposite side, bursting across like fast-moving clouds. Pairs of dancers, each grasping a single hand, pull away until they break apart and then, just as quickly, conjoin with a partner’s back leg bent in an attitude position.

Throughout “Solitude,” limbs are shown at brittle, broken angles or sometimes even like weapons. At one point, the women are carried offstage with a bent knee and a straight leg raised in the air; when their bodies are flipped, they’re like guns aimed into the wing. From time to time, the men pause to stand on one leg while crossing the other in front and holding it by the shin — balancing like amputees. When Ratmansky’s images register through the stage’s darkness, they’re chilling.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.