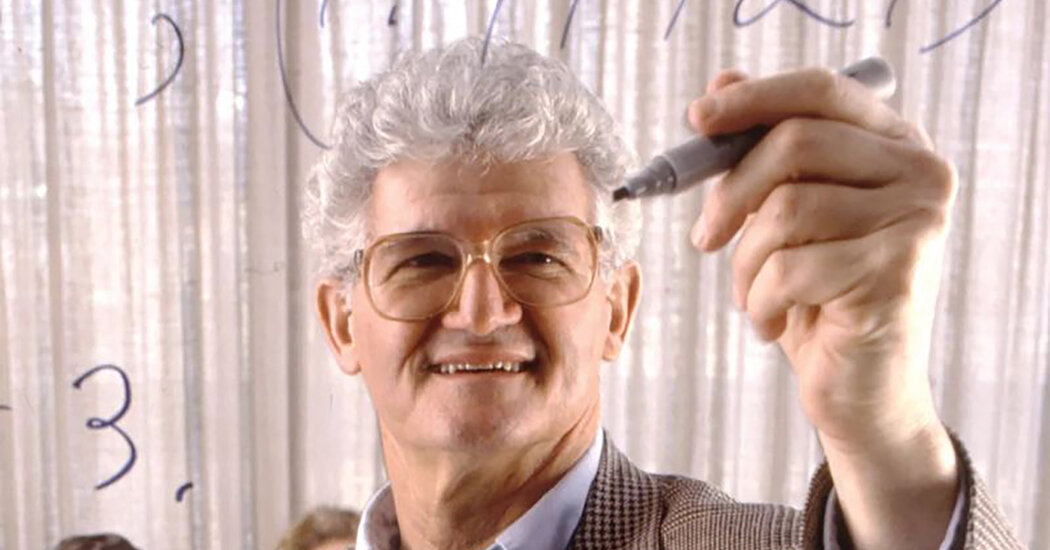

When Percival Everett’s novel “James” won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction on Monday, it seemed like an obvious choice. Everett’s subversive reimagining of “Huckleberry Finn” had already landed critical acclaim and a string of literary honors, including the National Book Award and the Kirkus Prize.

But it turns out that “James” was not the top pick among the Pulitzer’s five fiction jury members. It wasn’t even in the top three, according to three people with knowledge of the process, who were not authorized to speak about the confidential deliberations.

In a surprising twist, the prize went to Everett after the Pulitzer committee’s board failed to reach a consensus on the three finalists that the fiction jury initially presented — Rita Bullwinkel’s “Headshot,” Stacey Levine’s “Mice 1961,” and Gayl Jones’s “The Unicorn Woman.”

The process that led to “James” winning wasn’t a matter of the board imposing its own selection, but the result of a procedural backstop designed to give the board more choices when it reaches an impasse on the first crop of finalists.

In a typical year, one of the three finalists is chosen. But when the 17 voting members of the board deliberated on the fiction finalists last Friday, none of the three choices received a majority vote. At that point, the board could have voted not to award a fiction prize this year, as it has on rare occasions. Or it could vote to consider a fourth choice, which had also been chosen by the fiction jury.

In this case, the board voted to consider the fourth selection, “James,” which was submitted as an additional option earlier this year, after the board got the list of finalists and asked the jury for another title to consider. “James” got the necessary majority vote.

The procedure for widening the pool of candidates is outlined on the Pulitzer website, which notes that if the board is “dissatisfied with the nominations of any jury,” it can ask the chair for “other worthy entries.”

In 2012, no fiction award was given after the board failed to land on a winner — an outcome that outraged many in the literary world. In 2015, there were also four fiction finalists, with the prize going to Anthony Doerr’s “All the Light We Cannot See.”

Still, some observers expressed skepticism about this year’s process. In an article published on Monday on the website Literary Hub, the writer and bookseller Drew Broussard questioned whether this year the Pulitzer board had overruled the fiction jury’s selections of a “world-shaking all-woman trio of finalists in a year when one novel by a male writer has taken up quite a lot of the available oxygen.”

This year’s jury members for the fiction prize included the novelists Bryan Washington, Jonathan Lethem, Ayana Mathis and Laila Lalami, and the critic Merve Emre. Several of the jury members declined to comment on their deliberations; others did not respond.

Emre, who served as the chair of this year’s fiction jury, referred an inquiry to the Pulitzer board. An administrator for the Pulitzers said that the board doesn’t discuss its deliberations.

But Emre shared some withering views on the state of the book business on Instagram, where she noted that the jury waded through roughly 600 books and selected four that they felt exemplified the prize’s criteria as “distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life.”

“It was difficult to avoid fatigue and cynicism,” Emre wrote, adding, “American publishing is not in a healthy state; the more directly its judgments are determined by the market and the mass media — the more sources of funding, like the NEA, disappear — the sicker it will become: homogenous, inert, inexpert, cheap.”

Many in the literary world celebrated the Pulitzer board’s decision as a fitting outcome for a writer who has pushed the boundaries of fiction for decades. Much of Everett’s work has been published by independent presses, including “Telephone,” which was a Pulitzer finalist in 2021, though Doubleday, a major publisher, put out “James.”

The three finalists offer a snapshot of some of the bold and experimental work happening on the fringes of American fiction.

Bullwinkel’s “Headshot,” about eight teenage female boxing contestants in Nevada, was praised by the New York Times critic Dwight Garner as “so enveloping to read that you feel, at times, that you are writing it in your own mind.” In “The Unicorn Woman,” Jones, one of America’s most influential Black women writers, tells a surreal story about a World War II veteran who falls in love with a Black woman who has a spiral horn growing from her forehead and works at a carnival side show.

Levine’s novel, “Mice 1961,” published by Verse Chorus Press, introduces two orphaned sisters through the voice of their housekeeper. In a Washington Post review, the novelist Lydia Millet called Levine “a gifted performance artist of literary fiction, part French existentialist and part comic bomb-thrower.”

Levine was dismissive of speculation over this year’s fiction machinations, noting in an email that, at a moment when diversity initiatives and public funding for the arts are at risk, the Pulitzer Prize stands for integrity — a quality worth celebrating.

“Percival’s book is so important in this regard,” Levine wrote in an email. “Is this really the time to fuss about what might or might not be gender politics in a literary contest?”

Elisabeth Egan contributed reporting.