Becoming a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader Is Like Getting Into Harvard

As a way to dissociate from political news, I’ve spent the past week mainlining stories about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders; it started when I binged the new Netflix docuseries “America’s Sweethearts,” which follows the women trying out and training for the 2023-2024 squad.

I’m a New York Jew who got kicked out of ballet class when I was 4 because I lacked any discernible talent or interest. So I didn’t expect to fall in love with a show that is so steeped in Southern and dance culture. The Atlantic’s Caitlin Dickerson describes the old-school “cult of femininity” that requires these women to be “windup dolls of positivity.” In the docuseries, one bright-eyed, deeply earnest hopeful named Reece, trying out for the first time, exemplifies this ideal. She says that she wants the Lord to use her as a vessel when she dances: “I pray that whoever watches this one day sees him and not me.”

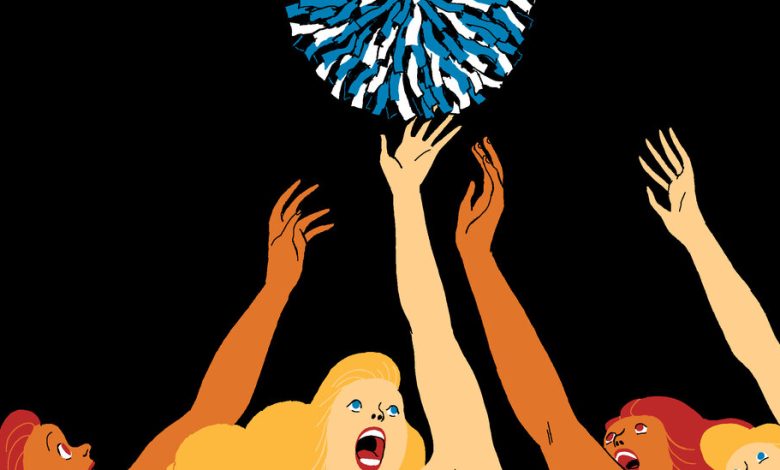

I came to adore her and the rest of these talented and beautiful women as they worked against incredibly tough odds — hundreds of women try out for the 36 spots on the squad. Because the newbies are competing for positions against veterans, the acceptance rate in any given year can be comparable to that of an Ivy League school.

The seven episodes of the Netflix series weren’t enough for me. So I watched a 2018 documentary about Cowboys cheerleaders, “Daughters of the Sexual Revolution.” I even started on the CMT reality show about the squad, “Making the Team,” which ran for 16 seasons, and is much less polished than the Netflix show.

Ultimately, I wanted a better understanding of how becoming a Cowboys cheerleader remains such a coveted prize, despite the low pay: Most of the cheerleaders have day jobs. In the Netflix series, we meet one of the squad leaders who is a nurse to a disabled little girl, and she rushes from her demanding job to cheerleading practice, getting by on very little sleep.

Much has been made over the years of the cheerleaders’ paltry compensation; one veteran describes the pay as what a full-time Chick-fil-A employee would make. And the cheerleaders make what they do only because a former cheerleader named Erica Wilkins sued the Cowboys in 2018 for back wages. As my friend, Sarah Hepola, who was a story consultant on the Netflix show, wrote in 2022 for Texas Monthly, after the suit, “The cheerleaders’ game-day pay went from $200 to $400, and rehearsal pay went up to $12 an hour.But that still isn’t a drop in the bucket given the Cowboys’ oceans of wealth.”