How Americans Justify Political Violence

In August 2022, I attended a gathering of right-wing grassroots organizations at a horse-show complex in Bloomsburg, Pa., a few hours’ drive east of where Donald Trump survived an assassination attempt last weekend. Everyone who went up to speak believed the 2020 election had been stolen from Trump, and now they were discussing what to do about it.

An evangelical pastor opened the meeting with the story of a pastor who fought alongside members of his congregation in the first days of the American Revolution. “Here’s a preacher training his people how to fight this ungodliness and wickedness, a real dictatorship,” he told the crowd. “Well, I talk to a lot of preachers today,” he went on, who were willing to “take up arms if they have to. And you know as well as I do, with what is coming, we may have to. Right? We don’t want to. But we may have to. And I believe the Second Amendment says we can.” Out in the crowd, a man had a sign depicting a rifle between a flag and a cross above the words “God, Guns, Guts! Keep AMERICA Free.”

Among the world’s historically stable democracies, America has a particularly complicated relationship with the idea of political violence. This is, after all, a country born out of violent struggle, as the T-shirts and bumper stickers and speeches at any Republican event endlessly attest. This is also a country where the major expansions of civil rights, from Emancipation to desegregation, happened under the fact or threat of state violence, and where few on the left are willing to categorically condemn violent protest in the name of social justice. It is a country where many still nod at Thomas Jefferson’s aphorism that “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants,” or to Malcolm X vowing “by any means necessary.”

The language changed, briefly, after the attempted assassination of Donald Trump. Immediately after Trump survived the shooting at a July 13 rally in Butler, Pa., both he and President Biden, two men who detest each other, spoke of unity. Biden, in a statement, said, “There’s no place for this kind of violence in America. We must unite as one nation to condemn it.” Trump told The Washington Examiner that he was rewriting his convention speech to focus on national unity, not Biden. “It is a chance to bring the country together,” he said. “I was given that chance.” But the truce didn’t even last the duration of the speech.

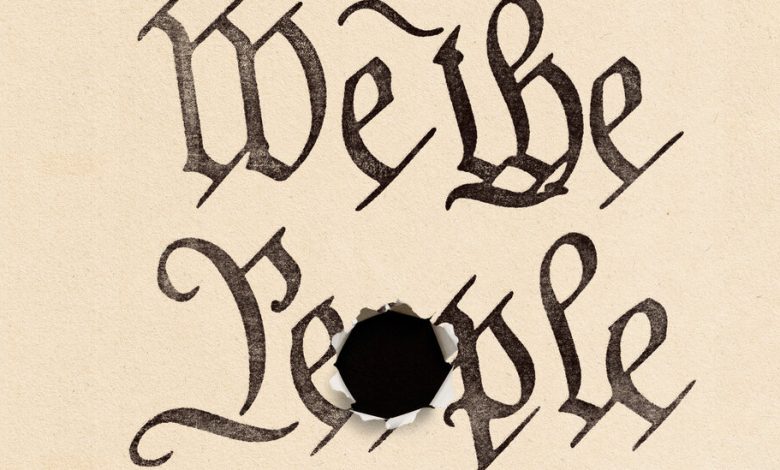

The assassination attempt on Donald Trump at a campaign rally in Butler, Pa., was followed by finger-pointing over the violent rhetoric that pervades American politics.Credit…Doug Mills/The New York Times

If condemnations of violent political speech ring hollow in the United States, it’s because they are. This is a country where the language of violence has become too deeply entangled with politics to disentangle with a few pro forma statements, and where a growing share of Americans are comfortable not just with rhetoric but with potential action. “They shot first!” a rallygoer in Butler told a BBC reporter immediately after the shooting. “This is [expletive] war!” A field director for Bennie Thompson, the Mississippi Democratic representative and former chair of the House Jan. 6 committee, was fired after posting on Facebook, “I don’t condone violence but please get you some shooting lessons so you don’t miss next time ooops that wasn’t me talking.” Liberal social media was awash in speculation that the whole thing had been staged.