Want to See This Film? Movie Studios Won’t Let You.

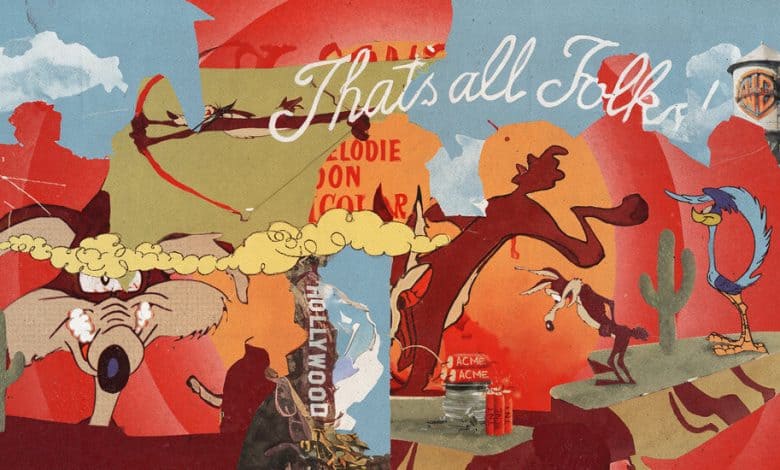

Credit…Illustration by Max-o-matic

In early February, strange news appeared about Warner Brothers Discovery’s plans for one of its films, a live-action-with-animation spin on Looney Tunes called “Coyote vs. Acme.” The studio did not plan to releas e the movie. It had tried to sell it to a third party — one industry report said Netflix, Amazon and Paramount were all interested — but no deal materialized. Audiences seemed unlikely to ever see the thing.

All this, industry watchers agreed, was not about cinematic merit. It was about accounting. Warner spent about $70 million making the film and might have gradually recouped that amount the usual way: by releasing the movie to paying audiences in theaters and on streaming platforms. But it might instead shelve the movie, interring it in a metaphorical graveyard and writing it off as a total, immediate loss, rather than absorbing that loss over quarters to come. One report estimated that this might net some $35 million to $40 million in tax savings, though a Warner spokesperson described that scenario as “inaccurate,” adding that no final decision has been made.

Studios have been doing this sort of arithmetic a lot lately. Over the last few years, Warner — which also owns channels like TNT and TBS and streaming platforms like Max — has whittled down its content-and-development holdings in an effort to reduce costs and chip away at its $45 billion gross debt. Near-complete movies have been mothballed, underperforming shows pulled from streaming libraries. Disney+, Hulu and Paramount+ have made similar decisions, roiling an already-baffling patchwork of streaming options. You can now watch an HBO property like “Westworld” on Amazon Prime Video but not through the network that made it in the first place.

The purgatory of “Coyote vs. Acme” galvanized audiences in an interesting way. Unlike other high-profile cancellations — say, the 2022 film “Batgirl,” axed during postproduction and called “not releasable” by the head of (the Warner-owned) DC Studios — “Coyote” was a completed film. It was also, by all accounts, good; Will Forte, one of its stars, called it “incredible.” This wasn’t the movie’s first funeral, either. News of its cancellation was first reported on Nov. 9 — followed, later that day, by an anonymous member of the movie’s production team posting a behind-the-scenes reel of the crew’s work on YouTube. The video was taken down after a copyright claim, but it had already revealed some of the ingenious mayhem that audiences would miss out on: squished cars, real clouds of dust kicked up by an animated roadrunner, charming prop renderings of the cartoons’ rocket skates and hand-painted signs. Say what you will about the artistic value of a film based on a cartoon, but this movie looked like fun.

The backlash to Warner’s reported decision might have helped prompt executives to try selling “Coyote” on the open market. A February report in The Wrap suggested that Warner rebuffed other studios after they failed to meet the asking price, said to be even higher than the studio’s own production cost. (The Warner spokesperson says no formal bid was made by any of the distributors who viewed the film for possible acquisition.) Another theory, floated to me by someone who worked on the movie, was that executives were concerned about embarrassment if “Coyote” turned out to be a hit for someone else. Either way, it felt as though the only parts of the film most people would see were promotional stills shared by Eric Bauza, the actor who voiced Wile E. Coyote. The movie was based on a 1990 New Yorker piece by the humorist Ian Frazier, which had Coyote filing a lawsuit over the indignities he had endured at the hands of Acme’s unreliable explosives and physics-defying spring shoes. In one image, Forte sits next to his cartoon client, who wears a familiar dopey expression as he endures this legal showdown with his mail-order tormentors.

You can picture the high jinks. In fact, a small army of designers, animators and demolition experts spent years imagining them. Those people want their work to be seen. A sizable audience wants to pay money to see it. Yet that mutuality isn’t enough. Millions of dollars and thousands of hours went into creating something that could simply vanish into accounting.